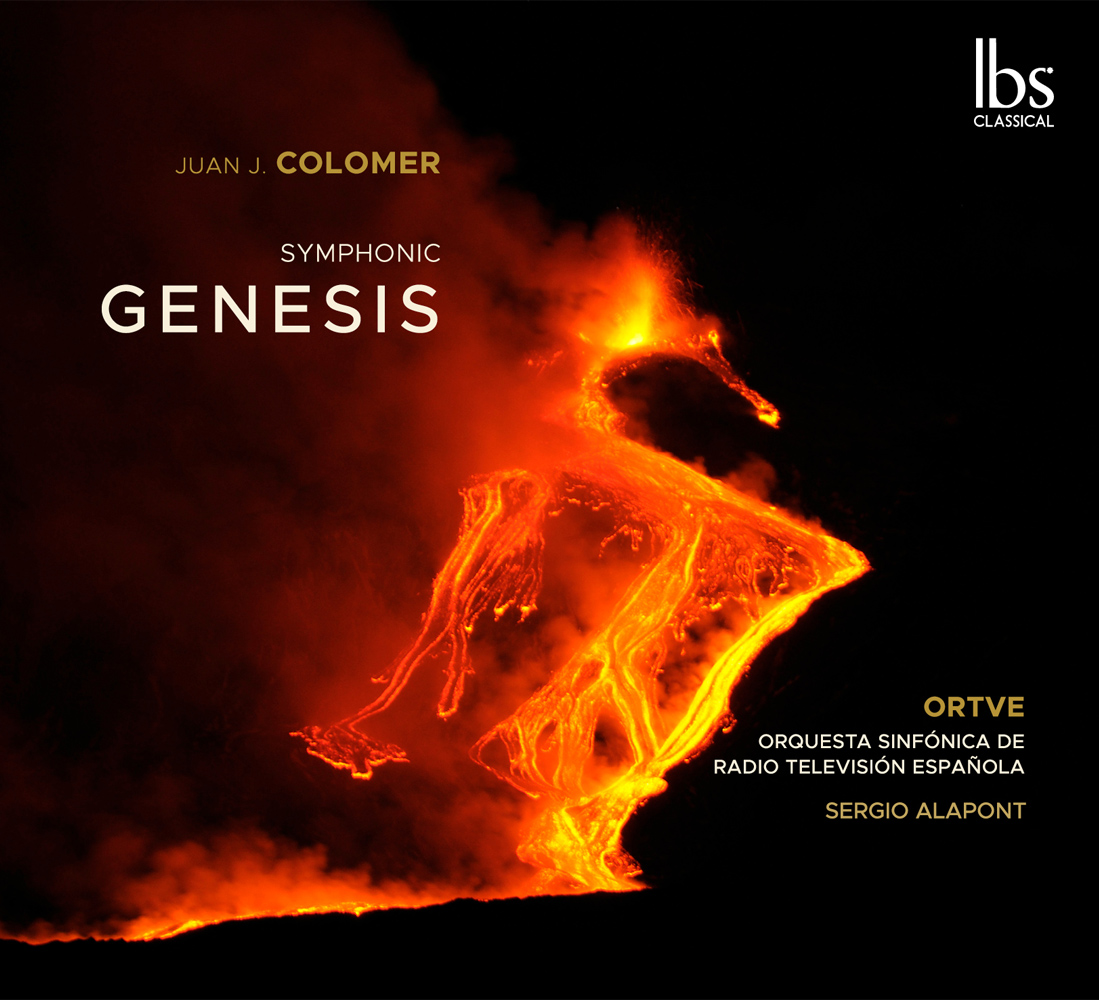

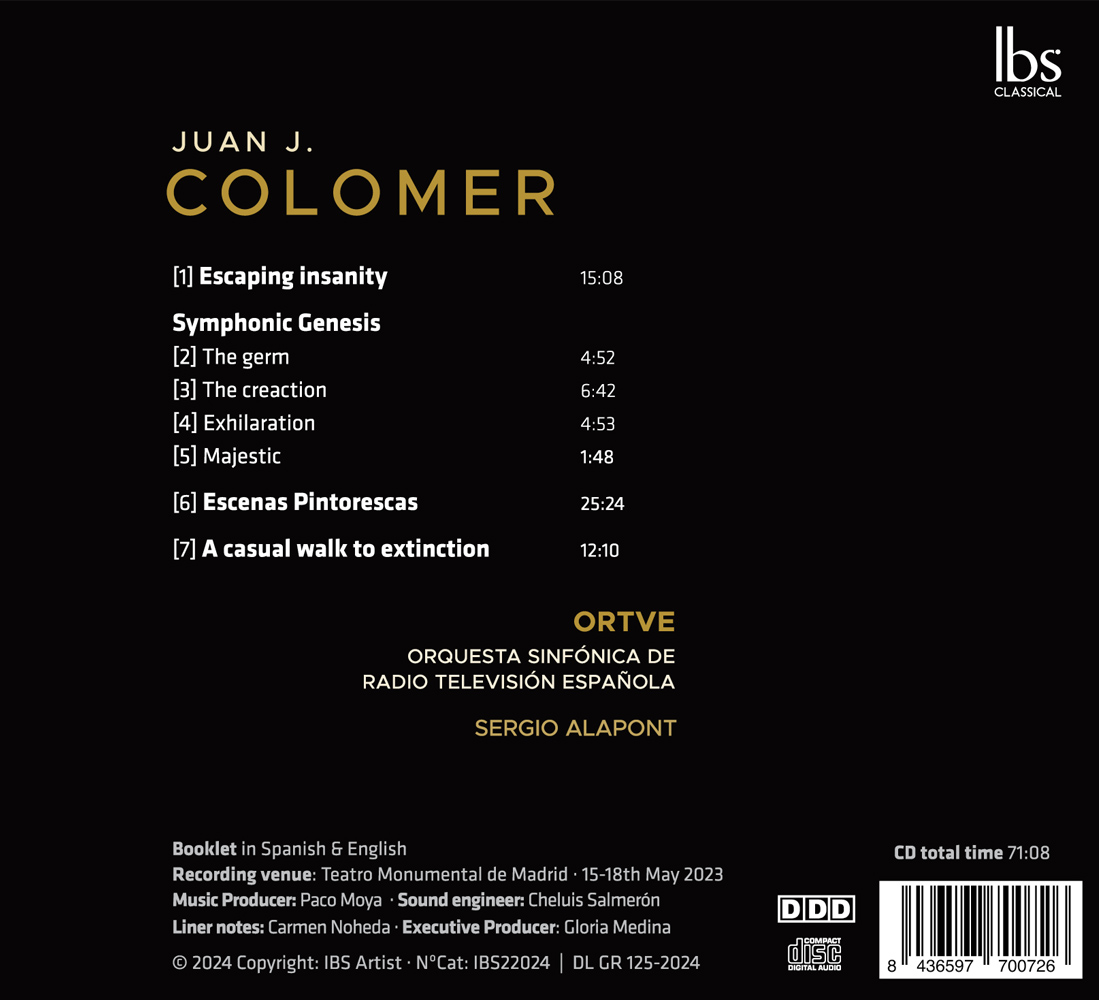

Symphonic Genesis

14,95€

The feeling is dispersed in the face of new beginnings. There is nothing in the music of Juan J. Colomer (Alzira, 1966) that does not speak about it: what he enunciates, what he leaves silent, what he does not completely conceal comes to intervene like the first day between those who listen to it. The luminous passages belong to the frank way in which an idea is shaped and its detours, where it appears without veils, as essential as the darkness that, from time to time, inhabits it. Both are openings to what his work is. We look for ways of access to the present and past, to small pieces of the map, to the abandoned territory or memory, to the contradictions it interrogates. Although this time it is titled “genesis,” Colomer modulates a thought without origin or end, within a perpetually restarted discourse.

BOOKLET:

14,95€

GENESIS

The feeling is dispersed in the face of new beginnings. There is nothing in the music of Juan J. Colomer (Alzira, 1966) that does not speak about it: what he enunciates, what he leaves silent, what he does not completely conceal comes to intervene like the first day between those who listen to it. The luminous passages belong to the frank way in which an idea is shaped and its detours, where it appears without veils, as essential as the darkness that, from time to time, inhabits it. Both are openings to what his work is. We look for ways of access to the present and past, to small pieces of the map, to the abandoned territory or memory, to the contradictions it interrogates. Although this time it is titled “genesis,” Colomer modulates a thought without origin or end, within a perpetually restarted discourse. This is how his invention lives outside. Perhaps in its living references, without dates or places exactly assignable, it retains the sense in which it inscribes, deprived of its ancient power, enigmatic connections, metamorphoses of times. For this reason, although it is about genesis, Colomer’s works become strange to the conditions of their creation, they are beyond the finished and the unfinished, they radiate as far as we like to imagine.

Sensitive to certain impossibilities, always in suspense, Juan J. Colomer fuels our question about what is expressed in the subtitle of A casual walk to Extinction (A casual walk to Extinction, 2023): “The curious case of the urgency that disappeared when humanity “He encountered the greatest challenge of his existence.” This “carefree walk towards extinction” is a call for uncertainty in the face of the climate emergency. Our disproportionate success as a species places us, without knowing it, in a new geological era capable of activating a devastating domino effect: a degree and a half more warming, expanding aridity, extreme weather phenomena, oceans with excess acidity – and plastics -, species threatened, a sea level that rises by millimeters, or five more weeks of summer on this side of the globe. The immobility around stirs up climate Armageddon and that is where Colomer critically confronts a passivity on a planetary scale.

With disturbing inertia, the existential threat occupies this slow and relaxed march that drags us: “despite some episodes of greater drama, on the whole it maintains a carefree air that contrasts with the imminence of the environmental challenge.” It may be a preventive attack, but Juan J. Colomer agrees with the observer’s impression of a kind of scorched earth tactic. That is why he points to the “apparent lightness” to surround it with an “ominous atmosphere, an underlying fatalism, as if the end of days were going to happen gently.” Without much fuss, this impossible journey de-dramatizes the evidence of failure “as if the habitability of the planet were something secondary to worry about in our free time, without the need to change our habits or destabilize the markets.” Signs of degradation that alternate with lavish summits, days that apparently changed everything and changed nothing. In the midst of the collapse, insufficient strategies for survival emerge. The roughness of the journey matters little, between departure and arrival, the white fissure of the flute or harp announces to us the only possible adventure: “our inability to put aside immediate interests for the sake of more ambitious and necessary common goals.” to be able to, at least, alleviate some of the devastating consequences that we are already beginning to suffer.”

In a frighteningly sane world, it is not enough to be wandering among (eco)anxieties, nor to quote that phrase that Einstein never said, nor wrote, to refer to madness. “Doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results” is the stubbornness that prevails in Escaping Insanity (Escaping the madness, 2021). Juan J. Colomer articulates a theme that he will continually repeat “with its essence unaltered, but with its changing circumstances in each successive repetition.” This call for temporally extended periods welcomes thematic and formal concerns: separating and recomposing is the modeled breath of Juan J. Colomer. The constant revision creates a precise network of materials that, at times, is reinforced in the foreground or camouflaged among the orchestral textures, “passing through different sections and contexts until reaching the end, where the cycle is broken, giving rise to a sensation of liberation.” The minimal performance, just an invitation to wonder in the opening string section, confronts us with the alarming possibility of “making the same trip every day or calling the same person several times at the same time and getting a different experience each time.”

Sometimes the conversation can be drowned out by passing sirens, the other person can get angry, happy, indifferent and so can you. The repetition of the same fact can generate boredom in successive repetitions, or create anxiety, frustration, satisfaction, etc., and that same change in our attitude not only differentiates it from previous instances, but also has the power to alter the result. of that same action.” Escaping Insanity is closing your eyes to see yourself in the well-known shadow of what is known, also in the tedious realm of memory that repeated hours bring, that climate of unactuality, of lost conversations, of smells without surprise that the senses reject, what has already been experienced. and dusty, in the air or in memory.

Sorolla also spoke about madness to his wife, Clotilde, when mentioning the “vibration of light” of the Mediterranean. Equally constant is the evocation of that same light as an intrabiographical extension for Juan J. Colomer. He had dedicated his first ballet to Sorolla (2013) and, beyond seeing with his own eyes that light that so many painters tried to capture, he opened his own, with the Mediterranean in the light, to the shine of California, to the immensity of the Pacific Ocean from the cliffs of Dana Point. He assures that there “the soft Mediterranean light and the vastness of the American landscape coexist in perfect symbiosis.” Colomer explores this “organic aspect” in Symphonic Genesis (2012), a score that celebrates the birth of the Dana Point Symphony Orchestra. Without pause, each of its four sections describe, in a continuous flow, subjective stages of its creation process: I. The germ, II. The creation, III. Rejoicing and IV. Majestic.

Carmen Noheda

Juan J. Colomer

Born in Alzira, Valencia (Spain), a region where every small town has at least one or two symphony wind ensembles, my first contact with music was as natural as playing with friends at recess. By age 16, I had a professional degree in trumpet and was a founding member of the newly created National Youth Orchestra of Spain. And even though performing was an exciting part of my musical experience, my real passion has always been creating music. For the next four years, I embarked on a dual master’s degree in composition studies and trumpet while teaching harmony, music theory and trumpet. I then moved to Boston to expand my musical palette at Berklee College of Music, where I specialized in film scoring.

Before I could finish my second semester, I started getting offers to score documentaries. I was intrigued, and I left Berklee for Los Angeles to learn by doing — a literal version of «fake it till you make it.» I enjoyed relative success for a few years, scoring over 30 films: shorts, features & documentaries, with actors like Margaux Hemingway, Roy Scheider, Daryl Hanna, Eric Roberts, Tia Carrere. As exciting as film was, I missed my real passion, which was classical music, in whatever label it came: contemporary, new music, concert music.

In my next chapter, I returned to my roots, writing concert music for wind & brass. It was during this period that I developed my own language and style, far from the constraints of the screen. It was a language defined by a consonance-dissonance duality, and through these conflicting elements, I created a narrative to immerse the audience in a personal journey I often describe as “out-of-context tonality.”My music was informed by — and often reflected on — the human experience and a search for raw expressionism.I was nominated in 2003 and again in 2004 for an Euterpe Award for best symphonic work by the Federation of Musical Organizations in Valencia, Spain.

I soon realized that what I had to say required more than wind & brass. My years of studying orchestration and analyzing scores paid off when I had the chance to orchestrate for Plácido Domingo. It was a dynamic collaboration that would span decades, reflecting his great range. In the 1990s, our collaborations included sporadic arrangements for the «Christmas in Vienna» concert series with the Vienna Symphony and the Three Tenors Concert in Paris in 1998 under the baton of Mto. James Levine.

Our collaborations were performed at other venues in the 2000s, such as «La Corona di Pietra» at the Arena di Verona, under the stage direction of Franco Zefirelli; the Three Tenors in Monterrey; the official Operalia Anthem, which Mto. Domingo conducts every year with the finalists of the contest; the «Concert of the Thousand Columns» in 2007 at the Mayan Pyramids of Chichen Itzá; and the recording of the CD «Spanish Passion,» where I orchestrated most of the pieces and won a Latin Grammy for Best Classical Album of 2008. That CD is also part of a “111 Years of Deutsche Grammophon” anthology, which the company selected as their most representative of the label.

After 15 years of working with world-class orchestras and conductors, I had a solid base upon which to apply to my own compositions. This became my sole focus. My compositions have been performed by the San Francisco Symphony, Simón Bolívar Symphony Orchestra, Russian National Orchestra, Los Angeles Philharmonic (Brass & Percussion sections), National Orchestra of Spain, City of Prague Philharmonic, Orchestra & Choir of Radio & Television, Seoul Symphony Orchestra, St. Petersburg Symphony, andOrchestra of the Valencian Community (Les Arts), at venues such Carnegie Hall, Tchaikovsky Concert Hall, Teatro Real, Adrienne Arsht Center, and Walt Disney Concert Hall. Over the years, I have published some of my works with BIM Editions of Switzerland, Editorial Piles, Rivera Editores and Tritó Editions of Spain. I also created my own publishing company, KA Music Publishing, which focuses primarily on digital downloads.

By 2010, I looked to challenge myself and find a new canvas for creative expression. My symphonic experience led me to my biggest project yet: In 2012, I was commissioned by National Ballet of Spain to write «Sorolla,» based on murals that the painter created for the Hispanic Society of America. Capturing Sorolla’s characteristic Mediterranean luminosity was essential, but the murals also possessed a more complex texture and depth, which I aimed to reflect. The music had to be flexible enough for dancers to express the power and subtlety of Spanish folklore with the contemporary imprint of a 21stcentury work.

Sergio Alapont

Cutting a magnetizing figure on the podium, Spanish conductor Sergio Alapont is known for his passionate, compelling and inspirational conducting and as one of the leading conductors of his generation.

Recent opera highlights include Nabucco at Teatro Real Madrid, La Bohème at Irish National Opera, his US debut conducting La Rondine at Minnesota Opera, a new production of Idomeneo at Opera National du Rhin in Strasbourg, L’heure espagnol and Gianni Schicchi at Opera Lombardia, Carmen at Opera de Oviedo, The Merry Widow at Fondazione Arena di Verona, Le nozze di Figaro at Teatro Comunale di Treviso and Teatro Pergolesi di Jesi, Poliuto at Glyndebourne Festival with London Philharmonic Orchestra or La Forza del Destino at Opera de Las Palmas. Season 2022-23 engagements include the opening night of the Festival de Pollença in a programme of Dvorák’s Eighth Symphony and Mozart’s KV. 482 Piano Concerto with Kristian Bezuidenhout and the Balearic Symphony Orchestra; a programme of Brahms and Beethoven for the Opening Season Concert at the Teatro Comunale of Sassari followed by performances of Don Giovanni; at Teatro Calderon of Valladolid he conducts Carmen. He makes his debut in Canada with the Orchestre Symphonique de Longueuil at the Maison Symphonique de Montreal in a programme of Spanish works by Palomo, Falla, Turina and Ravel. Later he will be conducting the Spanish Radio Television Symphony Orchestra. Next season 23-24 starts with La Bohème at the Irish National Opera, several concerts in France with the Orchestre National des Pays de la Loire (ONPL) – Nantes Opéra, La Voix Humaine with the European Youth Orchestra “Ferruccio Busoni”, and La Rondine at the Opéra Théâtre de Metz. Maestro Alapont’s recent appointment as Music Director at Orquestra Clássica do Centro in Coimbra takes him to Portugal for a variety of symphonic repertoire throughout the season.

Sergio Alapont’s studies took him to Valencia, Madrid and Munich before he continued his training at the Conservatoire of Music in Pescara with Donato Renzetti, graduating “Cum Laude”. He also studied with Jorma Panula at Royal College of Music of Stockholm, Helmuth Rilling at Bachakademie of Stuttgart, and Masaaki Suzuki at Bach Collegium of Japan. Additionally, he had the opportunity to assist Marco Armiliato at the Metropolitan Opera of New York, and Semyon Bychkov or Antonio Pappano in symphonic concerts. In 2016 Alapont won the Best Conductor Award at GBOSCAR– L’Eccellenza dell’Opera for his performances of Aida at Teatro di Sassari.

Equally strong in opera as he is in symphonic repertoire, Maestro Alapont has conducted many of the leading opera and symphony orchestras of the world, always winning outstanding reviews. Orchestras he has led include many in his own country, and guest engagements have taken him to the London Philharmonic Orchestra, Aalborg Symfoniorkester, Ulster Orchestra, Orchestre National d’Ile de France de París, Orchestre Symphonic de Bretagne, Orchestra of The Norwegian National Opera, The Orchestra of the Scottish Opera, RTÉ Concert Orchestra, Arena di Verona, Orchestra Sinfonica della RAI, Maggio Musicale Fiorentino, Teatro San Carlo di Napoli, Poznan’s Teatr Wielki, Spanish Radio Television Symphony Orchestra, Orquesta de la Comunidad Valenciana (Palau de Les Arts), Simfònica de Barcelona i Nacional de Catalunya, Orquesta de Cámara de Bellas Artes in México, and many others. He has conducted the leading artists of our time, including Kristian Bezuidenhout, Erwin Schrott, Gregory Kunde, Placido Domingo, Juan Pons, Celso Albelo, Anna Pirozzi, Désiree Rancatore, Ainhoa Arteta, Fabio Armiliato, Ewa Plonka, Maximilian Schmidt, Alexander Vinogradov or Lucio Gallo to name a few; his recordings are available on the labels of RAI, RTVE, RTÉ Ireland, Euroradio, Signum Classics, Ibs Classical and Universal Music.