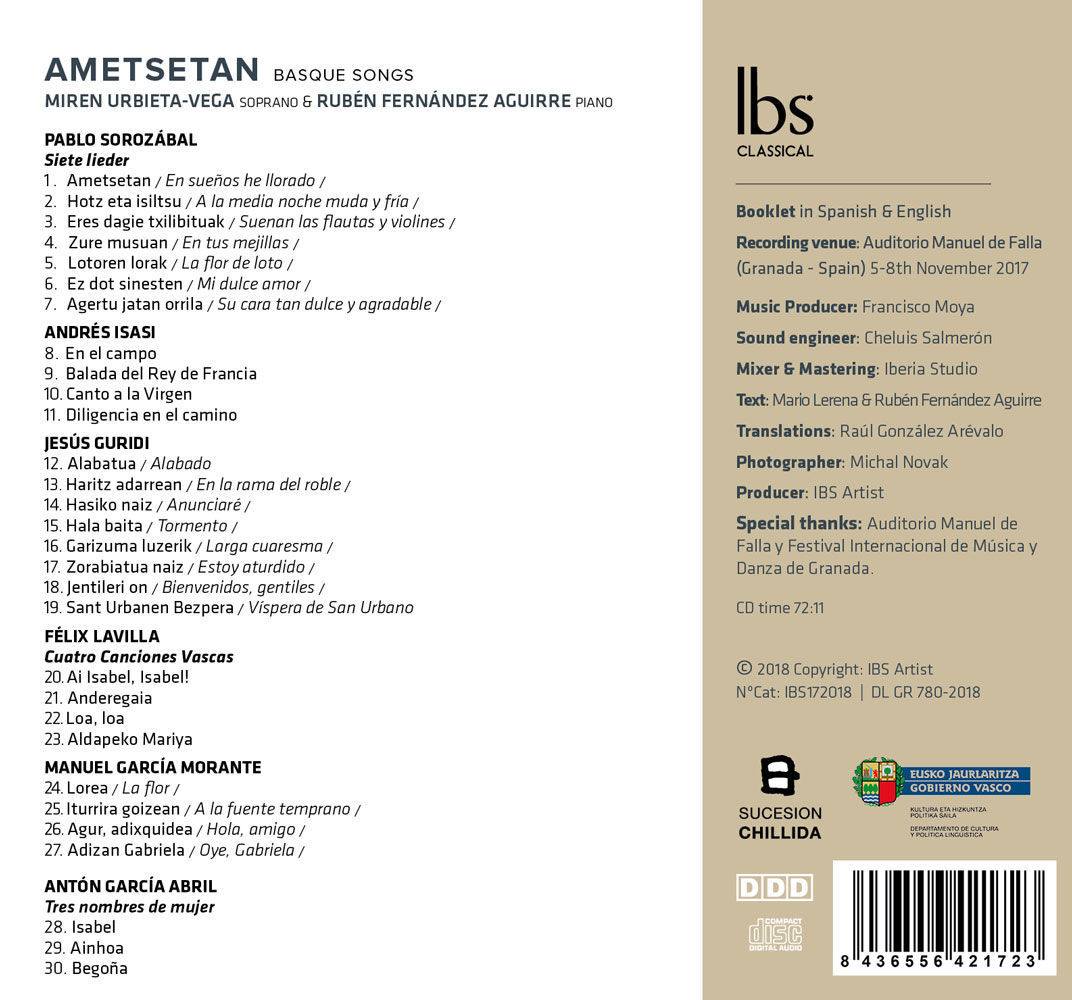

Ametsetan

14,95€

Miren Urbieta

Ruben Fernández Aguirre

The stunning economic development of the Basque Country after the end of the last Carlist War (1876) turned into an artistic flowering almost without precedent in the first decades of the 20th Century. Music, particularly, was promoted as an identifying attribute and a tool for civic progress. In a context of advanced “globalisation” of the Western culture, a constellation of local authors aspired to measure themselves on equal terms with their European counterparts, although without giving up neither their own personality nor their vernacular roots. Nevertheless, each of them faced such a challenge depending on their particular circumstance, sensitivity and idiosyncrasy.

14,95€

Andres Isasi

No doubt Andrés Isasi (1890-1940), a native of Bilbao, was the most engaged composer with the musical modernism of his age, turning to very different cosmopolite models to shape an exquisite and singular resounding art. A wealthy heir to a new aristocrat native from the mountains of Álava, he always enjoyed a total creative freedom. He studied with Humperdinck in Berlin and promoted his production in Germany, Sweden and Hungary. Isasi looked in the mirror of the prestigious and controversial painter Ignacio Zuloaga to claim the lineage of his inspiration without exploiting folkloric clichés. He wrote himself almost all the poems of his rich catalogue of Lieder, living up to an independent spirit that compelled him to some isolation, despite his early successes.

Jesús Guridi

The same intellectual and social elite that gave birth to Isasi’s first steps also supported with enthusiasm a native of Vitoria, Jesús Guridi (1886-1961), a member of a bourgeois family of notable musical tradition. As a matter of fact, in Bilbao they still remembered the longstanding work of his grandfather, the Aragonese Nicolás Ledesma, as chapel master. After a training stage in Paris, Brussels and Cologne, the young Guridi became for almost two decades the central figure of Bilbao’s musical life, before redirecting his career to the conservative but lucrative world of zarzuela. Nobody impersonated better the ideals of the rising Basque musical nationalism, of which his Ten Basque Melodies (1941), taken from the Azkue Popular Song Book, were an exemplary exponent. Some of his primitive vocal arrangements, published in 1930, can be tasted in the samples chosen for this recording, much less common than their orchestral version.

Pablo Sorozábal

By contrast, the proclaimed proletarian origin of Pablo Sorozábal (1897-1988) stands out. Son of a bertsolari (singer of bertsos, musical verses in the Basque tradition) of peasant descent, he breathed the refined air of the Belle Époque from the Orfeón Donostiarra and the Orchestra of the Grand Casino of San Sebastian. His subsistence jobs in cinemas, cafés and cabarets allowed him to assimilate a wide range of contemporary urban folklore, including a new rising style, jazz. Besides, his long stay as fellow in Germany during the 1920’s brought him closer to the aesthetic and ideological postulates of the German New Objectivity, with its characteristic conjunction of modernity, tradition and popularity. Precisely, his 1929 Seven Lieder stand in the intersection between popular and high culture, taking Heine’s poetry to the Basque sphere. His incisive and direct style, with a clear folkloric echo, already heralds the maturity of he who would become the ‘terrible child’ of the Republican lyric theatre. In their own way, the three musicians summarise a historical, social, cultural and geographical framework of thrilling eagerness, sometimes evanescent. Guridi and Sorozábal culminated their career in Madrid: the former acclaimed by the Academia; the latter blessed with popular success, although condemned to an inner exile because of his dissident and controversial nature. Only Isasi died, prematurely, forgotten, in his homeland.

Lavilla, Morante, García Abril

Can you imagine what it means for a young pianist to have as Maestro his own musical idol? That was, no doubt, Félix Lavilla for me, and I had the fortune to discover by his side a great deal of the Spanish repertoire for piano and voice (Granados, de Falla, Toldrà, Turina, Obradors, etc.), including his own compositions. Among them, his Four Basque Songs, defined by his daughter Cecilia’s words: “Written for my mother, Teresa Berganza, its melodies, rhythms and colours always fascinated me. When I had the possibility to sing them, under my father’s attentive and meticulous direction, I discovered more deeply their musical richness: the freshness of Ai, Isabel, the melancholy in Anderegeya, the intimacy of Loa-Loa and the vitality of Aldapeko Mariya. I carry them with me in my deepest and most beautiful memories. Manuel García Morante, composer and pianist for the unique soprano Victoria de los Ángeles, got an assignment from Félix Lavilla some years ago: “He gave me a phone call saying he knew and admired my Sephardic songs and proposed that I harmonized some Basque melodies he was going to send me. I waited for a period of time, but shortly after I discovered he had died. Keen to fulfil his assignment, I made contact with his daughter Cecilia and thereupon I harmonized twenty, dedicating them to Félix in memoriam. Basque popular songs had always captivated me for their emotional intensity and sharp contrasts. Giving a walk one night in Paris, after a recital with María Bayo in homage to Antón García Abril for his 80th birthday, the composer from Teruel surprised me mentioning that he wanted to dedicate me some songs. He only imposed a condition for such purpose: that I would look for some poems that would captivate him. “My meeting with Isabel, Ainhoa and Begoña, three stories of a passionate life, born from the message of three Basque poets, meant a moment I will never forget. The great pianist Rubén Fernández Aguirre introduced me to them, I discovered an inner world full of sensitivity that managed to charm me and I began to compose them straight away. With Three Names for Woman, as my missed Áurea baptised them from their birth, I happily fulfilled the debt assumed to compose a cycle for my dear and admired Rubén.