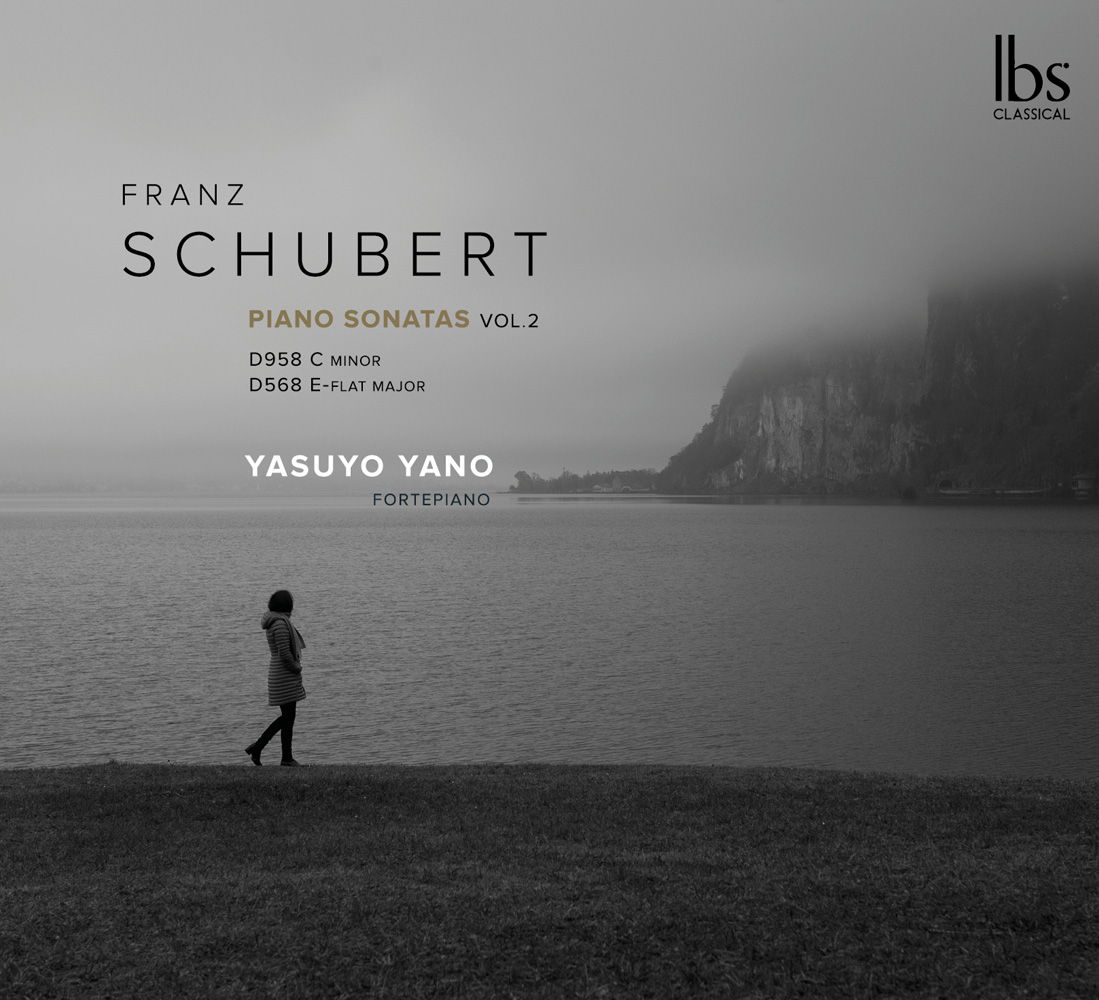

Schubert Fortepiano Sonatas

It can be speculated whether Franz Schubert, with the furious beginning of the Sonata in C minor, D. 958, composed in 1828, attempted to stand up compositionally against Ludwig van Beethoven, who was regarded as superior, to make a defiant “I can do that too” confession, as it were.

This view is sometimes reinforced by the fact that Schubert might have felt liberated by Beethoven’s death in 1827 and would finally have been able to step out of his shadow. Certainly, however, this interpretation does not do Schubert justice when one considers that many of Schubert’s very great works were composed before then – e.g. he composed the “Trout Quintet” D. 667 in 1819, and in 1824 the Octet D. 803 and the string quartets “Rosamunde” D. 804 and “Death and the Maiden” D. 810 – where would Beethoven’s “shadow” be felt in these masterpieces?

One can imagine that Schubert had had a certain, perhaps even great shyness towards Beethoven. Strangely enough, there is no record of a meeting between the two, even though they were both working in the same city at the same time in the same, relatively rare composer’s profession, and both were thus well known and respected.

On closer inspection, Schubert’s compositions hardly appear as a will to distinguish himself from Beethoven, or even as an attempt to outdo him. His enormously extensive catalogue of works suggests that Schubert had spent almost every spare minute of his short life composing. Unlike Beethoven, who had to work out his compositions with countless notes, Schubert’s music almost always flowed effortlessly from hand to paper. By composing what he heard inwardly, Schubert was able to preserve his independence. The fact that he was exposed to a certain influence from the universally respected Beethoven can be regarded as quite normal and actually unavoidable, although it remains open how conscious Schubert was of this influence in his inspirations.

More than the music of others, texts, primarily poems, were an important source of inspiration for Schubert; he was inflamed by literary-poetic models, his soul literally merged with them. Finally, it can be said that Schubert embodied his Biedermeier era in an almost archetypal way, since the escape into the idyll, into the private sphere, was the essential feeling of the time. Beethoven was still rubbing up against the courtly representation of the late 18th century, whereas Schubert was probably too busy migrating into his inner self to care about rivalries.